March 11, 2007

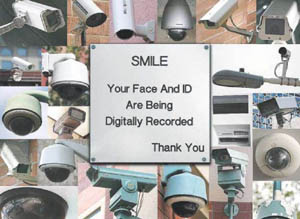

Ever get the feeling you’re being watched?

J. Craig Anderson, Tribune

It’s not just paranoia. You are being watched. The period following Sept. 11, 2001, has been a technological Renaissance Era for agencies and companies that monitor, track and record the activities of everyday people.

It’s not just paranoia. You are being watched. The period following Sept. 11, 2001, has been a technological Renaissance Era for agencies and companies that monitor, track and record the activities of everyday people.

By comparison, the legal system charged with regulating these new surveillance systems is still in the Dark Ages, critics say, with technology outpacing lawmakers every step of the way.

Low-cost digital video cameras, Internet monitoring software and myriad consumer tracking systems that convert behavior into data have raised new questions about how far a society should be allowed to go in scrutinizing its members.

In short, when innocuous surveillance becomes ubiquitous, does that make it insidious?

Police organizations stress the benefit of increased surveillance in solving crimes, but others say the loss of privacy to law-abiding citizens has been too great.

“Do we want to live in a place where every move, every action, every thought, perhaps, is monitored and regulated?” said Torin Monahan, an Arizona State University professor researching the effects of surveillance on communities. “Do we want to live in a society that is totally devoid of trust?”

THE SURVEILLANCE AGE

Take a walk along any downtown street with your eyes fixed on the light poles and rooftops overhead.

You will invariably see a cadre of cameras trained on publicly accessible areas such as roadways, sidewalks and parking lots.

In downtown Tempe, the Tribune spotted 68 such cameras, all plainly visible from street level. In a comparably sized section of Old Town Scottsdale, there were 23.

In general, the larger and more dense a city’s downtown area, the more cameras passers-by will find, researchers say.

The New York Civil Liberties Union recently completed a camera-mapping project in New York City and found that between 1998 and 2005, the number of street-level, outdoor surveillance cameras had jumped from 769 to 4,468.

The group’s concern, as expressed in a report it released in December, is the effect those cameras have on expectations of privacy.

“Have you ever attended a political event? Sought treatment from a psychiatrist? Had a drink at a gay bar? Visited a fertility clinic? Met a friend for a private conversation?” says the report, written by Loren Siegel, Robert Perry and Margaret Hunt Gram. “Might you have felt differently about engaging in such activities had you known that you could be videotaped in the act — and that there would be no rules governing the distribution of what had been recorded?”

Similar reports in other major cities indicate a growing concern among civil rights organizations that public surveillance has gone too far, and regulators not far enough.

“People often say, ‘If you have nothing to hide, what are you worried about?’ ” Monahan said. “But just because you have something to hide does not mean you are a criminal.”

Monahan, who teaches a class on the impact of surveillance and is hosting an international gathering of researchers at ASU this week to discuss the issue, said the visibility of cameras often shifts the focus away from more widespread forms of electronic surveillance most people don’t see.

So-called “post-optic surveillance” includes global positioning system locators found in many cars and cell phones, radio frequency identification tags used in retail security and other systems, and even discount cards used by major grocery chains that track and record buying habits.

“We focus on the cameras because they’re so obvious, but it’s drawing our attention away from these other systems,” Monahan said.

LAWMAKERS OPPOSE LIMITS

In Arizona, efforts to limit government surveillance on the masses through legislation have met with resistance, said Sen. Pamela Gorman, R-Anthem.

Gorman argued Thursday for a bill she sponsored that would have forced law enforcement agencies to purge vehicle and driver information collected during an automobile theft investigation in the event that police determined no crime had occurred.

The bill, SB1636, was soundly defeated, with opposition votes coming from both Democrats and Republicans.

“If you live in a police state, who even cares if your car is stolen?” Gorman said in an interview after the bill failed.

Gorman said she was shocked that many of her Republican colleagues favored allowing police to amass personal data unrelated to a criminal investigation.

“The Republican Party is supposed to be the party of small government, unobtrusive government,” she said.

Marc Rotenberg, executive director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center in Washington, D.C., said government officials at all levels have been reluctant to limit the scope of their surveillance activities.

“I think politicians have always tried to exploit public fear, but we have to make rational decisions,” said Rotenberg, whose nonprofit organization seeks to limit government surveillance. “It should not have to be a trade-off between personal freedoms and national security.”

But there’s an indisputable fact that cannot be overlooked, said Lt. Paul Chagolla of the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office: Surveillance has been crucial to placing criminals behind bars.

“Government surveillance footage is for a purpose — to capture a crime as it unfolds,” Chagolla said. “The cameras don’t lie.”

But despite their value to prosecutors, Monahan said studies show that most surveillance systems are not monitored in real time and therefore are only useful after the fact.

“Cameras tend not to have a preventive effect on crime,” he said.

CRIME AND DATA

George Orwell was close when he imagined a future saturated with surveillance, but his assumptions about the motivation for monitoring were far less accurate.

In reality, it is overwhelmingly private interests that have employed cameras, sensors and trackers to protect assets or to streamline the methods of acquiring more.

The problem, Monahan said, is that such information has a tendency to fall into the wrong hands, and companies have been far more skillful at gathering data than they have been at protecting it.

“When it’s commercial surveillance, we don’t see it as oppressive, generally speaking,” he said, “but the downside is the stockpiling of these huge databases that are not regulated very well.”

Even the government has, at times, failed to protect its sensitive data.

In May 2006, the theft of computer data inside the home of a Department of Veterans Affairs employee resulted in the largest unauthorized release of Social Security numbers in United States history. The electronic files contained names, birth dates and Social Security numbers of about 26.5 million military service members and veterans.

When it comes to video surveillance, however, the overwhelming majority of footage is generated by private companies for purposes of private security. The video only makes its way to law enforcement agencies if it ends up being used as evidence in a crime, Chagolla said, and even then there are rules dictating how — or if — it will be released to the public.

“Obviously you would not want to release video footage of a person being victimized, a sexual assault or homicide,” he said.

But the rules get murkier when footage contains someone engaged in legal but potentially embarrassing behavior.

“That’s where the privacy issue comes into play,” he said. “When I’m not sure, I’ll ask for direction — I’ll ask people in the media that I respect.”

Public records laws require that police disseminate such footage upon request unless there is a compelling reason not to do so, Chagolla said, but those reasons are not specified.

“The public records law is written in black and white, but it’s not black and white,” he said.

Critics such as Monahan, Rotenberg and Gorman believe those laws should be more specific, and that government needs to act fast before the gradual proliferation of surveillance systems catches too many law-abiding citizens in embarrassing acts.

“We’re not going to wake up one morning and find that there are cameras on every corner,” Gorman said. “Big Brother is going to creep up on us one peep at a time.”